Let’s cut to the chase…

Do you like research?

If you don’t like research, then hell no, you shouldn’t pursue a PhD. Oh, but you want a high salary? Then you should definitely pursue a PhD! JK, pursuing a PhD for salary’s sake is probably one of the worst moves you could make. More on this below.

But I want money!

Take the following case study: I graduated from undergrad in 2016 with my BS in chemical engineering. I then completed a one-year master’s program (for which tuition was covered and a monthly stipend was provided, btw) and took a job at Corning Inc. I was hired in at the company’s lowest level, A-band (salary/promotion bands are A-F at Corning and then follow a more sophisticated system) and worked for around 3.5 years.

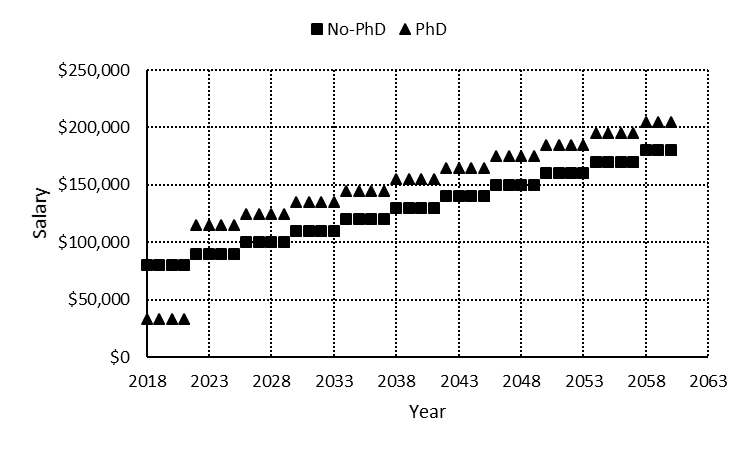

My salary over the 3.5 year period was around $80,000/year. Please reference this salary in the context of geographical location and consider that I received cost of living raises each year of around 3%, if I remember correctly. Please also consider that bonuses are not included in the above number (neither personal nor shared bonuses).

I hadn’t received a single promotion during my time with the company (which I was pretty pissed about considering my high level of performance), but I would have expected one by the end of my last year there (had I not left the company). It would be reasonable for me to assume that that promotion would have come with a salary increase of $10,000, yielding a salary of $90,000 five years after I graduated with my BS.

So, in five years after graduating with my BS, I hypothetically achieved a salary of $90,000 and earned a salary of $80,000 in the four years prior.

Now, had I went straight on to complete my PhD in the five years following completion of my undergraduate degree and joined the same company, I would have likely started at a salary of $105 – $115k per year.

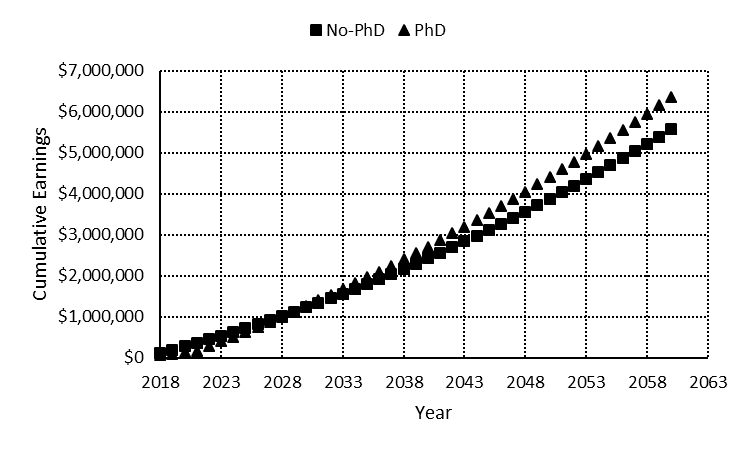

At this point you’re probably thinking “see, I told you, the PhD is worth it!” However, something you probably aren’t considering is the cumulative wealth trajectory. See the plots below for that (keep in mind the one-year master’s kind of throws things off).

The payoff on cumulative earnings doesn’t happen until around twelve years after graduating from undergrad, or eight years after earning a PhD, even with the generous estimate of a $115k starting salary post-PhD. In addition, it is well within the realm of possibilities that you could match or even exceed the PhD cumulative earning’s trajectory during the entire period of study through more frequent or more lucrative promotions without a PhD.

What about job satisfaction?

Although it is generally (but not always) true that a PhD will earn you a higher cumulative wealth by the time you retire, another important consideration is job satisfaction. If you hate doing research, is it really worth it for you to spend five years of your life (at likely 40-50+ hours) doing it to earn a degree and then continuing to do it for 50+ years until you retire?

You might think it is, but to tell you the truth, money isn’t always all it’s cracked up to be. You see, I would argue that the most precious thing in your life is your time (I have an entire post dedicated solely to the importance of time).

If you hate your life five out of seven days per week, it seems very unlikely to me that any sum of money could “make up for” the amount of time you piss away being miserable. What would you do with the extra money anyway? Go on weekend shopping sprees? You’d only get two days per week to do that.

If additional money can in fact bring you enough happiness to “make up” for hating your life five out of seven days of the week, I would argue that you have some character development work to do.

On a side note, if you really want to make big bank, get your MBA.

Anyway, the above was a big digression. Sorry about that.

Now if you love research and hate late stage chemical engineering work such as process engineering, you should definitely pursue your PhD. This is pretty straightforward.

But what if I don't know?

The folks who have a real conundrum on their hands are the folks who enjoy both research and non-research based chemical engineering work and the folks who are missing meaningful experience in either research or non-research. After all, how can you tell if you like something if you’ve never done it? One great way to figure out what you’d like to do is to work before you commit to attending graduate school.

But if I work, I won't want to go back to school!

This is the line I’ve heard probably a billion times from people who are wary of working before attending graduate school, and I have several points to state in response to this.

My first point is around your life objective. My guess is your objective in life is to be happy. If you graduate from undergrad, get a job, are happy, and have no desire to return to school, what’s wrong with that? You’ve accomplished your life objective. Why dwell on it?

Now, what you’ll probably say is “but what if I could be happier with a job that requires a graduate level education?” That’s a tricky one, and unfortunately, I don’t really have a good answer for you. The only way to answer that question for yourself is to earn your PhD, get a job, and then check your level of happiness afterward to compare. Yeah, not great, but as they say, hindsight is 20/20 and life don’t come with a manual.

From my personal experience, I think that if you’re destined for graduate school, you’ll return to school, regardless of the figurative barrier that might exist and stigma (I say that jokingly) that comes along with being “going back to school” again. Also, working before pursuing your PhD can be super beneficial and I strongly suggest it for anyone who has reservations or is uncertain regarding what the right move is coming out of undergrad. Quite honestly, I might even suggest it for everyone. I can’t see any harm in working for a couple years before starting graduate school. Maybe I’m missing something?

There is a caveat though: if you do choose to work before pursuing your PhD, you should try to make that work count. What do I mean by this? I mean you should deliberately seek exposure that will help you gather the additional data you need to decide whether to return to school or not.

For instance, if you’ve only ever done research in undergrad, you should try a job in late stage chemical engineering such as a process engineering role. If you’ve never done research, join a research lab as a research assistant or associate scientist. Identify what experience you need to answer your lingering questions and get that experience.

When I was working in industry, I had a personal rule that I would never turn down a project unless it was something I had done before and knew with certainty that I wouldn’t like. The breadth of exposure I gained was enormous.

When it came time to decide whether returning to school was the right move for me, I presented the 10+ efforts I had supported to my mentor and asked him to categorize those efforts. My mentor categorized three of the efforts as “PhD projects” (work that typically would be given to someone with a PhD), about five of the efforts as “non-PhD projects,” and a couple of the efforts as having components of a “PhD project.”

What did I find? My three favorite projects were “PhD projects,” the couple of efforts I enjoyed had components of a “PhD project,” and the projects I strongly disliked were categorized as “non-PhD projects.” This data strongly supported my decision to return to school.

The TLDR:

The TLDR on the above is the following:

- If you hate research, do not pursue your PhD

- If you love research and hate late stage chemical engineering work (such as process engineering), pursue your PhD

- If you like both research and late stage chemical engineering work, or if you lack experience in one area or the other, work for a couple years and gain the experience necessary to figure out if grad school is the right move for you

OMG! I don't know what to do, everyone else has it all figured out!

The notion that “everyone else” has it “all figured out” is a big load of shit. The thing is, it’s impossible for somebody to have it “all figured out.” For someone to have it “all figured out,” he would have had to either live all the possible lives he could live and pick the one he liked the most, or have gotten really lucky and made all the right moves with a figurative blindfold on. The former is impossible and the latter is extremely unlikely.

For whatever consolation this may provide, I’ve lived my life like a ping pong ball. I started undergrad as a biochemistry major. Why? Because I liked biology and chemistry. I then switched into chemical engineering at the end of my sophomore year. Why? Because I thought maybe I’d like chemical engineering more. I then decided to enroll in a one-year master’s program. Why? Because I thought it would be challenging. I then took a job at Corning Incorporated. Why? Because I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do and desired additional exposure. I decided to return to graduate school. Why? Because I thought pursuing my PhD would be fulfilling.

What might you notice about the above? Perhaps that I’ve lived my life in a non-linear fashion and that I chose to partake in each of the above experiences because of what I hoped each experience would offer me in and of itself, not because of where I hoped each experience would get me.

In short, I’ve lived my life by trial and error. I’ve worked on projects I loved, and I’ve worked on projects I hated. Never in my life have I had everything “planned out” with details and dates and where and with who. The obsessive planners you’ll encounter throughout life are often admirable, but also sometimes intimidating in a way: they always seem to make me feel like I’m behind the eight ball. However, based solely on my personal experience, I’ve noticed that these obsessive planners tend not to cope well when life throws them curveballs. Perhaps this is because these obsessive planners feel a need to re-plan their entire life after each curveball, which is probably exhausting. I largely live my life day-to-day.

Closing words of wisdom

I’ll close with the following. This is your life and nobody else’s. Make your decisions and commit to them fully. Don’t let others dissuade you from doing what you think is right for you, and never do something just because “that’s what everybody else does.” If everybody did what everybody else did, we’d still be living in caves. There will always be people out there who doubt your abilities, people who will say you’re making the wrong moves, and people who will hate on your accomplishments. Those people are nothing more than white noise and they ain’t worth listening to, so fuck ‘em.